You have to keep reading.

It’s hard when you have a daily word count and the world is on the type of fire best viewed from a constantly-refreshed timeline, but you have to keep reading. It’s like broccoli (I do not care for broccoli). It’s good for you.

I’d been on a craftwork kick for some time this summer, so when I found myself in Barnes and Noble, I moseyed on to their “writing on writing” section. The pickings were slim, but I came across the DIY MFA, a workbook promising the results of a Master in Fine Arts program without the financial and emotional consternation that follows actually enrolling in one. I quite like creator Gabriela Pereira’s approach—read with purpose, write with focus, and build your community. To read with a purpose, she proposes, one must have a robust personal library of the following:

Type of Book | Reason |

|---|---|

Competitive | Read these to figure out what’s out there and how your WIP can stand out |

Contextual | Books that are similar in theme but aren’t necessarily a direct competition (includes research) |

Contemporary | New releases in your genre; not necessarily competitive or contextual |

Classics | What it says on the tin |

So, I got to shopping.

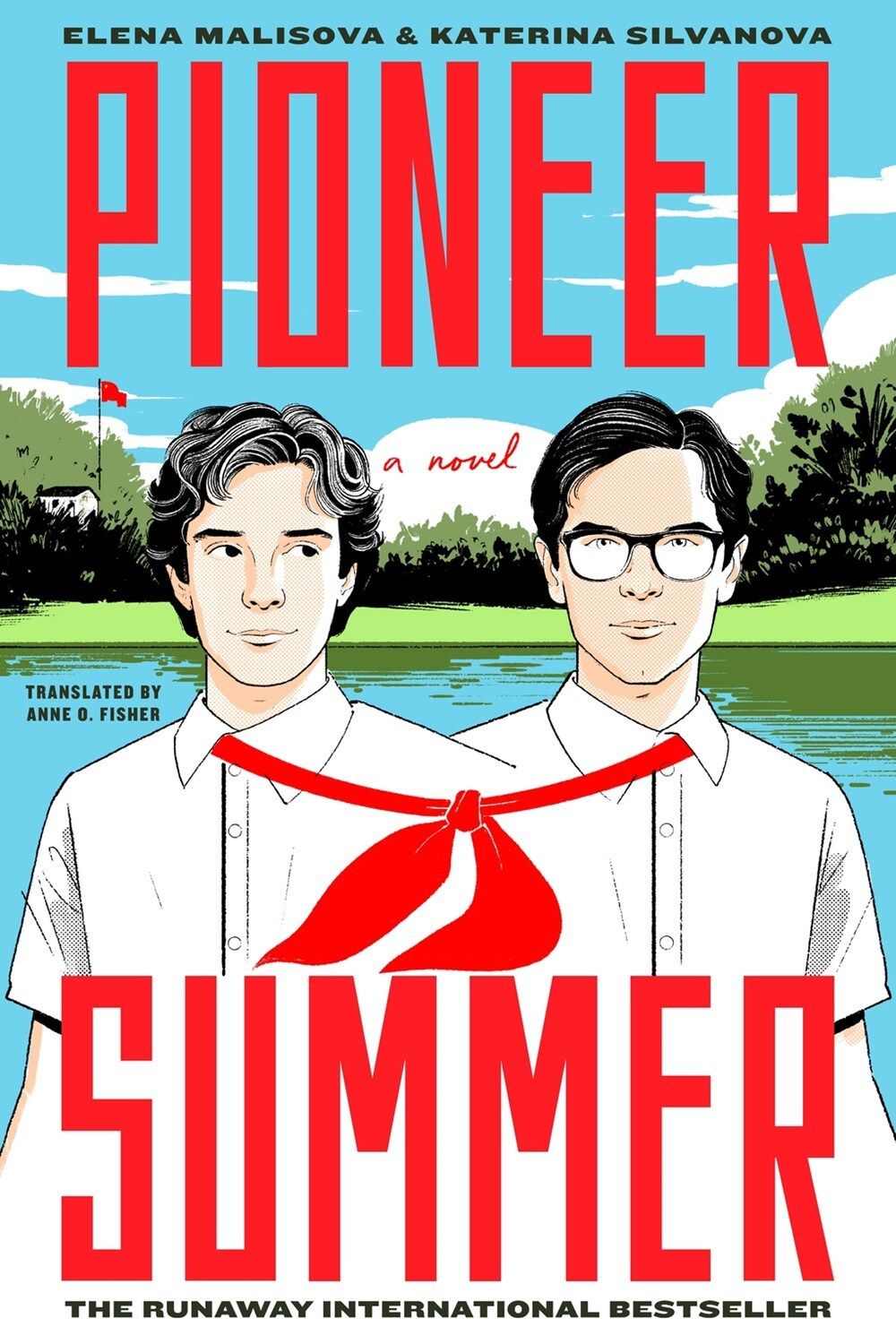

Over the next few weeks, I picked up Pioneer Summer and Alchemised, both of which I consider “Contextual” reads. Pioneer Summer (original title: Leto v pionerskom galstuke), because it is a historical fiction, queer romance that takes place in Soviet Ukraine—topical for a few reasons—and, Alchemised because it is the latest high profile fic-cum-ofic novel published. There was lots of subsequent discourse about filing the serial numbers off fics and how publishing houses market these books. I have a lot of thoughts on this that I’ll get to…eventually. I didn’t realize that Alchemised was over 1,000 pages until I bought it 😭

Pioneer Summer isn’t much of a slouch either at 441 pages. Also, apparently, this BookTok sensation stirred up its own discourse. It was first published in Russian in 2021, and the country has extremely strict anti-LGBTQ+ laws. The jacket says the book’s publication “catalyzed one of Russia’s largest-ever crackdowns on LGBTQ+ representation” and sorry chat I have to press X to doubt on that assertion. It seems more like promotional puffery than anything else. Regardless if it jump started any kind of legislation, the book did cause an uproar. One of the book’s two authors in fact fled to Germany after receiving hate and harassment (the other author is a Ukrainian woman who returned to Kharkiv following Russia’s full-scale war in February 2022).

I consider this a “Contextual” read because it captures the ordinary life of Soviet children from the perspective of former Soviet children. There is an authenticity here that is hard to find in nonfiction and easy to supplant into my own characters’ perspectives. It’s also completely outside of my genre (queer romance vs literary fiction) but is tangentially related to my themes (growing up, reconciling the past with the present, ordinary lives against extraordinary circumstances).

Now, I’ll be frank. I didn’t much care for this book. Not only because it’s not my typical genre, but because I found the second act bloated, the characters dull and flat, and the translation difficult to get through. There are also issues However, I don’t want this to be book review for a book review’s sake. I want to take the time to unpack and understand what I found unsuccessful and what lessons I can take into my next draft of The Places We Call Sacred.

I’m going to use my own silly framing device for analyzing books I call the 4PO Method, that is People (Characters), Plot, Prose, Presentation (Themes, motifs, other ways that the author(s) convey meaning), and Other Observations (in this case, it will be the translation). This will contain spoilers! So, if you want to read this book for yourself, consider yourself warned. Without any further ado, let’s get into it!

About

Pioneer Summer is a 441 page, young adult, coming of age, romance novel that takes place at Camp Barn Swallow, the site of a Young Pioneers summer camp. The story follows Yura Konev as he reminisces on his time at the camp—all of the activities one normally does like calisthenics, assemblies, and the Summer Lightning capture-the-flag battle, but also the play he had a significant hand in executing, and Volodya. Volodya is the older boy that he fell in love with, the boy who changed the trajectory of Yura’s life, the boy whom he’s looking for in the present day. It’s one of those “the summer everything changed” kind of books, a tried and true subgenre within young adult.

People

Yurka Konev is sixteen years old. He should have graduated from the Young Pioneers long ago, but due to outside circumstances, he was “held back” in previous rounds, making him the oldest among the children by two years. With this, and a fist fight with the son of the city’s executive committee chairman (a “typical privileged nomenklatura prick,” Yurka says on pg. 133), he returns to Pioneer Camp with a reputation (“Because you’re a parasite and a vandal (pg. 17)!”) and a chip on his shoulder (“You’re still worthless, an utter mediocrity (pg. 145).”). Yurka is a pianist and failed to enter conservatory. Since the fight and the failure, he has not touched a piano since. Yurka is an outsider looking in, both shunned by and shunning Soviet society in the mid-1980s. He is cynical of the whole Soviet system and “doesn’t like it when people live just by inertia (pg. 34).” Everyone, for the majority of the book, is telling Yurka to “grow up.”

By contrast, Volodya Davydov is a college freshman at the prestigious Moscow State Institute for International Relations (MGIMO). He is an upstanding Soviet man. Yurka describes him: “[Volodya] could have stepped out of a Communist Party poster: tall, trim, self-possessed, dimples in his cheeks, skin glowing in the sun (pg. 10).” Volodya became a troop leader to earn a good character reference for Party membership. He’s strapped with Troop Five, the youngest kiddos from ages seven to ten, as well as the drama club. He’s sweet, awkward with the kids, and a bit neurotic, but he’s got that rizz that makes all the camp girls want him. He also harbors little faith in the Soviet system as well (“I want to leave,” he interrupted (pg. 136).”), but cares very much about what others think of him (“That’s stupid! Everyone can’t be wrong.” (pg. 304). He needs his reputation after all to become a Party member, and what can sully a reputation faster than being discovered as a homosexual (“I’m not normal (pg. 303).”).

The Romance

It’s a heavy thing, to be queer in the Soviet Union. “There aren’t even any books about it in the USSR,” Volodya tells Yurka (pg. 300). “There’s just the entry in the handbook of medicine saying that it’s psychological, and then the statute of the Criminal Code.” Volodya is keenly aware of the consequences, while Yurka is petulant in his affections:

“‘You think this is…disgusting?’ said Yurka, flabbergasted.

He thought about it. Okay, maybe from the outside they really did look strange. But that was from the outside. Being ‘inside’ their relationship, their friendship, maybe even their love, felt completely natural and wonderful to Yurka. Nothing was better than—nothing could be better than—kissing Volodya, holding him, waiting to see him again.

‘I don’t think so,’ said Volodya dejectedly. ‘But other people do…’”

And:

Volodya’s cheeks turned pink, and Yurka was abashed. He’d wanted to say different words to Volodya—ones that did not, of course, include “troop leader” and “older brother.” But there were people there. And Masha. Yurka was trying to say “I love you” without saying the word “love.” He was so sick and tired of all this damned secrecy…

This tension between Yurka and Volodya is clearly framed to be a plot driver, and while I can respect a queer character who is so certain in who they are and what they want, society be damned, it seems odd that Yurka doesn’t realize even a fractal of the danger he and Volodya are in. Several times in the novel, he even chastises Volodya for being so paranoid. I can also understand that he’s a horny and hotheaded teenager, but the depth of his ignorance comes across as stupidity. Yurka is Jewish, which appears as a plot point and offers a glimmer of character insight before disappearing into the background. I would expect a character already experiencing marginalization to be at least somewhat aware that his attraction is a secondary (dare I even say intersectional) marker for marginalization.

Volodya remains self-shamed through the entirety of his and Yurka’s summer romance. It is understandable, even if it makes the story more start-and-stop than I would like. It’s a clear and rich motivator, and adds a depth to his attraction and his action upon that attraction that is…sadly lacking in the narrative. Given that this book was written by two authors, it would have made sense to tell this story in dual point of view, but alas, this is not even Volodya’s worst infraction. I will talk about this more in the section on plot, but Volodya’s coming to terms with his queerness happens off screen in a series of letters he left for Yurka (and the reader) to discover in a time capsule. In the span of three pages, after 400 pages of self loathing (and self harm too!), we go from:

“But I don’t know how to deal with it. I know now that it is incurable. I look at other people like me and I don’t feel any hatred toward them, or at least I don’t think so. But other people being this way are one thing; it’s different when it’s yourself.”

to

“No matter where I am, I feel detached from the world, and everywhere I go, I’m different from other people—and not in a good way, either. I’ve accepted myself and I don’t fight my perversion anymore.”

and

“I’d really like to be able to say I have no regrets. But alas, that’s not the case. I do have regrets—painful ones. Not about you, but about what I did to myself in ‘89. If I’d known what the consequences would be, I would never have agreed to go get treatment and I would’ve strangled that ‘doctor’ with my bare hands.”

and finally,

“My only real relationship started late, when I was 31…I got tired of his vacillating and ended the relationship…I didn’t miss him, just the closeness…I forgave myself and accepted myself. And damned if I don’t feel so much better now.”

If we understand character arcs as a tension between “need” and “want,” then this is a really poor rendering of Volodya’s arc. It contributes to the book’s difficult pacing (which I talk about below), that the payoff to this struggle happens, I cannot stress this enough, 400 pages after the character’s introduction and off screen. This story would have been served so well by having two point of view characters.

Other Characters

There are other kids that populate the camp, like Masha Sidorova, a senior camper described as “a Chekov’s gun (pg. 42)”, and Ira Petrovna, Yurka’s stern troop leader. There are kids like Sasha Pcholkin, who can’t pronounce his Rs properly, and because of his rendering on-page, comes across as much younger than he actually is. Little Octoberists are seven years old at the youngest. Sasha often comes across as five or six. There are also the campers Ksyusha, Ulyanna, and Polina, girls that Yurka collectively calls the Pukes, for…some unspecified reason. Literally.

For some reason, Yurka and the girls had disliked each other from the get-go. He remembered them as snot-nosed ten year olds; now they had grown up into actual young women.”

Growing up is a theme that runs through the novel like the river that serves as a motif for the romance. Many of the characters tell Yurka that he needs to grow up and stop acting like a child. It’s interesting, looking back at my notes for this post, that all of the named female characters, in addition to Volodya, are described as “grown up.”

Yurka looked hard at [Masha]: in the intervening year, she’d changed completely. She’d gotten taller and thinner. Her hair now hung down to her waist, and she’d learned to flirt, just like a grown woman. Now she was sitting all proud and pretty, her back straight and her legs long and tan.

Ira Petrovna is referred to throughout the novel by her first name and patronymic indicating respect, and Yurka compares her both to the stern teacher stereotype by calling her “Marya Ivanova” (pg. 14) and as a mother, “What a great guy he was: not only had he hidden behind his troop leader’s skirts, he’d also let her down (pg. 25, emphasis mine).”

It’s also interesting that despite these descriptors that the female characters are quite immature, and if I may—hysterical. Masha gets the worst draw here. She is desperate for Volodya’s attention to the point that she stalks him, and it’s through that stalking she that discovers the forbidden romance (pg. 280). In fact, Volodya says later that, “She just doesn’t know how she should love. She’s in despair (362).” I also just realized in writing this that she isn’t a troop leader, but a regular, not-held-back Pioneer. She’s fourteen years old. Oh my God, was there no one to take this actual literal child aside to say, “Hey! Knock it off! Your feelings are misplaced!”

The Pukes, also members of Troop 1, are described often as shallow, into hair and makeup, and scheming, trying to get Volodya to go to a camp dance so they can dance with him (pg. 50). Ira Petrovna is described as “indulgent, even in her strictness (pg. 14),” and when she is on page, she is more likely than not scolding Yurka.

The disparaging descriptions of the female characters go beyond either gay dismissal or “ew girl cooties,” which it reads like at times (because the girls are fourteen while Yurka is sixteen??) and lands straight at misogyny. It is quite disappointing, especially considering that the book was written by two women.

Lessons Learned

Characters must have a clear internal arc that is echoed through the external plot and that arc must be satisfied before the last 20 pages of the story.

Marginalized and minority characters must exist beyond their stereotypes. While there are women out there whom we find annoying, they are not just “hysterical harpies.” Make sure you have a sensitivity reader on hand to provide guidance.

Provide nuance to character renderings. Characters shouldn’t obviously be The Rival, The Mom, The Kid Character.

Children exist on a spectrum and just because they are not a teenager does not mean that they act like they are five. Adjust character descriptions and renderings appropriately.

Plot

I don’t remember where I got this from, but if we understand plot as moments of increased tension and stakes that are eventually resolved, then the novel presents three plot lines:

Yura searches for the time capsule (present time)

Stakes: If Yura does not find the time capsule, then he will understand his relationship with Volodya as truly done and over.

Yurka falls in love with Volodya (flashback)

Stakes: If Yurka does not fall in love, then he will not reconcile his past

Stakes: If Yurka does not fall in love, then he will not “grow up” into a man who is confident and secure in his sexuality.

Stakes: If Yurka falls in love and other people know about it, it is more than just his reputation on the line.

Yurka helps Volodya manage the drama club’s stage play commemorating 30 years since the camp’s namesake and young partisans defended their land from Nazi invaders (flashback)

Stakes: If Yurka does not help Volodya, then he will be kicked out of the Pioneer program.

Stakes: If the play is not a success, then Volodya will be considered a failure.

These elements have the clearest stakes and rising tension. Everything else that happens at camp is just Stuff Happening, and there’s a lot of Stuff Happening at camp. The amount of Stuff Happening really slows down the novel’s pacing (discussed below), and I wager is part of the “Telling vs. Showing” problem (also below).

In trying to present itself as a story recalled, there’s a rhythm of “this happened and then this happened and then this happened.” Isn’t it natural to remember pointless or meandering details, especially from your childhood? Yes. This is natural, but it is not narrative.

There’s also a missed opportunity to more closely align the play with the overall story being told. I think the authors attempt to do this—

“Yura what’s with the anti-Soviet antics?!”

Yurka turned around and looked at him, nonplussed.

Volodya closed the distance between them and said right in Yurka’s ear, “You do get how that looks from the outside, right? You’re insulting the memory of the leader of the revolution.”

Yurka scoffed. “Oh, to hell with that revolution! To hell with Leonidovna and her partisans and Fascists! That’s all she and Palych ever do: paint some people as all evil and some people as all good. […] “I’m saying that Germans are people too, like us. They’re not all scum.”

[…] Volodya paused. He exhaled in frustration. “Look, you have to have better judgment. I know you want to think and speak your mind freely, and you can, but just not here! You have to adjust your behavior to fit the situation.”

—but it’s a very unsuccessful rendering.

Given how much this conversation echoes Volodya and Yurka’s conversation later about how things look in and out of their relationship, I have to conclude that this was intentional.

This is extremely clumsy, in effect, comparing queerness with Nazism (it’s also just abjectly false, too. Germans knew what was happening and Germans were largely fully bought into Nazi goals. I am begging everyone on my bloody hands and knees to read Bloodlands). Not to mention that by this point of the story, Volodya knows that Yurka is Jewish. That he is given the role of Nazi soldier seems Very Stupid! and Very Insensitive! Certainly something that would warrant a conversation with your boyfriend!

It’s not brought up at all afterwards in the text.

Conversely, the authors do successfully connect queerness with the play’s live soundtrack as well as music in general. Since failing to enter the conservatory, Yurka has denied himself the pleasure of playing piano.

Volodya went silent. Yurka stared at the river. He was recalling how hard—almost impossible—it had been after that to force the music to be silent and then to learn to live in that silence. To this day he still hit his own hands and squeezed his interlocked fingers together until they hurt—whatever it took for them to unlearn their habit of drumming out his favorite works.

The descriptions of this denial echo how Volodya denies himself full acceptance of his queerness:

Volodya was still as a statue, holding his right so low over the boiling water that the skin was turning red…His face was contorted, as though by a spasm, and his glasses were fogged over…”Move your hand! You’ll burn it!” Volodya swatted Yurka’s hand away from the heat. “I’m—it’s okay for me. I’m…tempering my hand.”

As the romance between them blossoms, Yurka opens up about his past and about music. It becomes more apparent that Moonlight Sonata is the wrong song to accompany the performance, and Masha is the wrong person to deliver the music.

He listened for a moment, then all but dropped the script: Masha wasn’t playing the Moonlight Sonata. She was playing another melody, one that was far more beautiful, a melody Yurka loved very much but hated even more. The unfamiliar feeling grew even more painful as he recognized Tchaikovsky’s Lullaby through Masha’s labored, stiff rendering…Masha was playing it wrong.

Masha represents an immature love. She doesn’t know how to love. She doesn’t know how to play the piano artfully. On the contrary, “…wherever Volodya was, there was always music (pg. 207).”

Lessons Learned

Trim the fat. The novel does not have to exist strictly as a vessel to dispense a plot line, but stakes and rising tension must be felt in each sentence on each page. Ask yourself, why is what’s happening, happening?

Do not try to “nuance” the Nazis.

Prose

The prose is rough. There are three hurdles you have to get over to make it to the end. First is the abundant gerunds (was + verb-ing), the second is the bizarre authorial choice to tell rather than show the story unfold, and third is the equally baffling choice to write almost exclusively through idioms and cliches.

Gerunds galore

In her notes, translator Anne O. Fischer states that: “I believe that US readers who choose to read a story set largely in Soviet times, with largely Russian-speaking characters, are by definition interested in tasting the Russian-language flavor of the text.”

I really wish she had taken a different approach.

In Russian grammar, the emphasis of tense is not when on the timeline it occurred, but whether or not the verb is complete. Aspect. Both on chital knigu and on prochital knigu translate directly to “he read the book,” but the former is more like, “he was in the process of reading the book” and the latter is, “he finished the book.” Whether he is finished for today or finished the book in its entirety is context dependent. The point of the matter is that he is no longer reading.

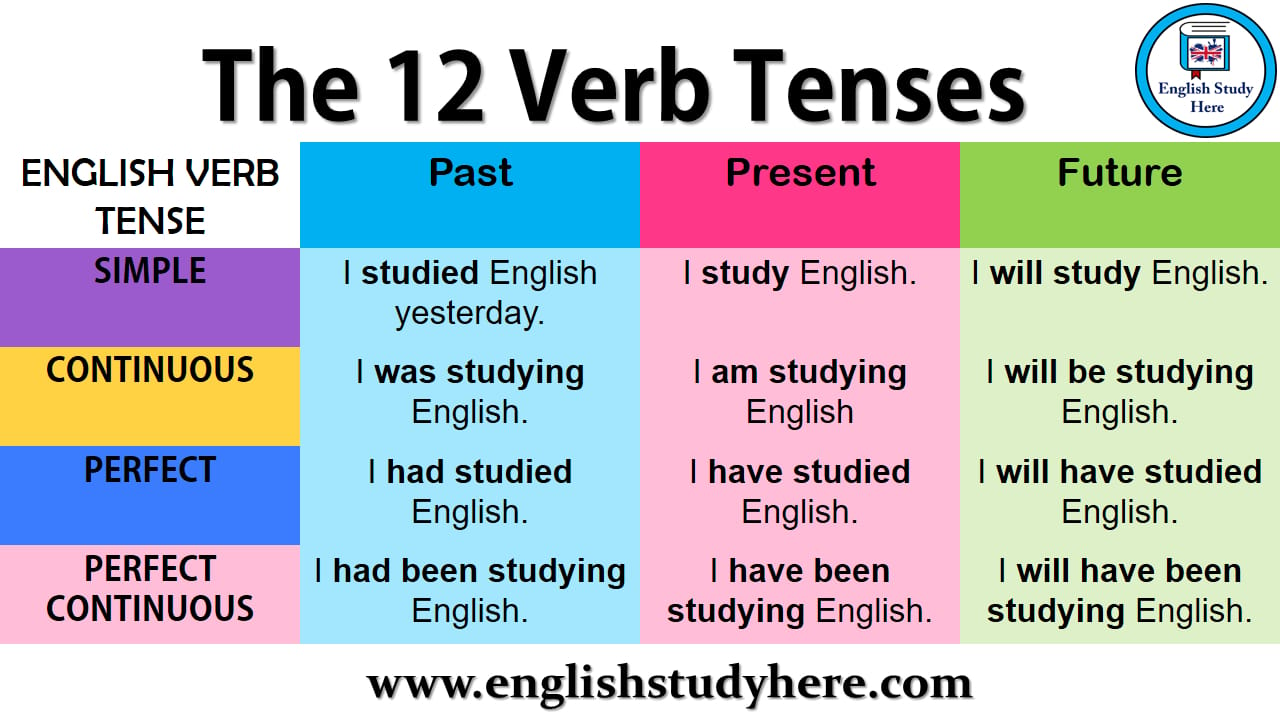

This stands in stark contrast to English grammar. A byproduct of German, it is, of course, very concerned with when exactly something happened. That’s why there’s eight thousand verb tenses.

I do not wish learning English as an adult on my worst enemy

Because things just kind of generally happen in the past unless otherwise specified, you can get translations that do a lot of to be [verb]ing.

It is exhausting to read. I got so frustrated with this convention that to continue reading, I just started underlining any instance of “was doing” I saw. Don’t get me wrong, this is not the mark of a bad translation, on the contrary! This is an extremely faithful translation. This is what Russian feels like in my English-speaking mouth. It just makes for a very tedious reading experience in English!

English’s many verb tenses also makes for some unique irregular verbs (they’re all irregular). There are a few sentences that contain the verb, “sneak,” like this one, “Suddenly, everything had gone dark: somebody had sneaked up behind him and covered his eyes with their hands (pg 255).” It should be “had snuck up behind him” right?

Telling vs. showing

I understand that there is a different paradigm between English-speaking narratives and everyone else when it comes to showing vs. telling. It’s why anime is Like That—where the main character’s thoughts are narrated all the time. It’s not wrong, it’s not bad, it just is. I get that.

However.

Having read other translated-from-Russian books, I know that having your hand held so tightly by the author that your fingers are white from lack of blood is not the norm.

Yurka was at the piano before he could think about it. He reached out and turned on the lamp. As soon as he saw the keys, illuminated by the warm yellow light, panic seized him again.

“This fear is nothing compared to the horror you went through yesterday. And this feeling of your own worthlessness is nothing compared to the humiliation of Volodya pushing you away,” he encouraged himself. It was a strange sort of encouragement, but it worked.

The whole book is like this. Like the above “was [verb]ing,” I started to underline instances of this to keep myself moving forward, like each egregious description was a rung on a set of monkey bars.

Another byproduct of all this telling is that beats are either suddenly dropped on the reader or resolved immediately. The passage below is a really good example of this. The bus number’s three digits is enough for Yurka to not only notice but to be amazed by it, but by the end of the paragraph, it is an unremarkable detail.

“Crossing the highway was easy. So was memorizing the bus schedule. There was only one bus that came all the way out here: the 410. Yurka was amazed. This was the first time in his life he’d seen a three-digit bus number. […] [I]n the part where the bus number was written, there was a wide crack, so maybe it wasn’t 410 after all. But that didn’t matter. The main thing was that the end station was in the city.”

Other honorable mentions:

It was at the last minute now, the best minute, Yurka’s favorite part; it was so innocent and good. Unlike Yurka. (pg. 152)

Yurka had been launched into outer space and was floating there, enchanted by the yellow and white sparkling of stars. Except that in his outer space the stars were sounds (pg. 210)

What an intimate act that turned out to be, taking Volodya’s glasses off! (pg. 248)

Cliches, idioms, adverbs

I have to go back to my other Russian-translated texts to see if this is a pattern across the board from this language, but my God is there so much lazy figurative language and confusing authorial choices here that further dilutes the reading experience:

Yurka was tousled and engaged; Volodya was calm and cool and a little bit condescending. (pg. 104)

But the fish weren’t biting. So far the only biting was Yurka. He was biting the inside of his cheek, trying to stay awake. (pg. 127)

Yurka flinched involuntarily. (pg. 199) (me, screaming at the book, as opposed to what???)

Yurka, eyes bulging, was in turmoil, barely breathing. He blinked. He squeezed Volodya’s fingers…[He] couldn’t believe what was happening…[Volodya’s] pupils were huge as he gazed urgently at Yurka, holding Yurka’s hand. Volodya was holding Yurka’s hand! (pg. 214)

His wildly joyous thoughts made his heart do a frenzied tap dance. (pg. 239)

Some folks call sleep the “little death,” and, indeed, everything around them really did seem to have died away (pg. 246). (This just confuses me to the cellular level. This is not what un petit mort means!!! What are you talking about????)

Yurka’s first reaction was panic. Next came paralyzing horror. It felt as though the entire earth had fallen out from under his feet, as though the stage were breaking apart, as though everything around him were turning upside down (pg. 280).

Presentation

Pacing

All the aforementioned creates a novel with pacing as slow and lumbering as I ran in high school.

The authors’ telling as opposed to showing present scenes as individual slides that do not necessarily congeal together into a single narrative. Characters “all of a sudden” or “suddenly” remembering things drives plot points. Arcs, as I’ve mentioned above, are traversed in single sentences. Scenes start and stop. This is weighed down heavier by clunky prose and a desire to retain the “flavor” of the Russian language in English.

After growing closer to Volodya, Yurka began enjoying the theater more too. Although the place had bored him at first, it became special to him after a couple of rehearsals. It was fun there, and comfortable, and Yurka felt he was a full-fledged member of the team.

Hearing him, Yurka suddenly remembered: “Volod! Whil you were running the rehearsal, Petlitsyn tried to get me to get up in the middle of the night and go toothpaste the girls.”

“Oh! I meant to tell you: yesterday after supper I was going to the cabin and I saw Olezhka…it turns out that this whole time the kids have been teasing him because of his r’s and now that he has one of the main parts, they’ve really started picking on him.”

Note: This is a pretty significant event that contributes to the “preparing for the play” thread mentioned earlier. It’s just mentioned as an afterthought and there’s limited build up. I don’t remember too much about kids bullying Olezkha/Sasha.

The pacing labors under the authors’ insistence of guiding you through each and every cobblestone on the story’s path.

But to force himself to touch the piano, Yurka had to conquer a fear that had seemed unconquerable. Although what was that sharp, prickly fear compared to this, the leaden, aching dread Yurka had been feeling all night last night and all day today? What’s more, he’d been afraid for so long.

And then Yurka remembered what had happened yesterday. He hadn’t forgotten, of course, but now he remembered it even more clearly—so clearly that he felt Volodya’s breath, Volodya’s smell, on his lips. A warm feeling spread through his chest, and Yurka went still, a stupid expression on his face.

As Yurka let the music in, it passed through him, washing away his emotions. The sounds spoke for him, and he knew that the person these feelings were for would understand. The music was saying everything for Yurka: the love he felt, and the yearning he would suffer, and how fiercely he didn’t want to part, and how unbelievably happy he was to have met this person.

It drags because we learn the same lessons again and again and again. As stated above, Volodya and Yurka argue about the goodness and the appropriateness of their relationship from its forming to their departure from camp. There are at least three fully rendered scenes where this argument happens. There isn’t an escalation of tension or in stakes. It’s just this:

Volodya: I like you but we can’t. It’s gross and wrong. I’m a monster. :(

Yurka: I don’t care. >:( I like you and I like me liking you. >:)

Lessons Learned

Each scene should raise the stakes, increase the tension. Don’t waste readers’ time by returning to well-tread discussions unless there’s a reason to.

Trust your readers. They are capable of picking up what you, the author, are putting down.

Themes

Growing up means taking on responsibilities, to yourself and to others. Yurka is told repeatedly by troop leaders and senior staff that he is a hooligan and a menace and that he needs to grow up. Through his relationship with Volodya, Yurka takes responsibility for his feelings and his actions: playing piano again, being active in his community, and steadfastly choosing to love whom he wants to love.

Live with intention. Yurka states that he can’t stand people who live through inertia. His character arc is marked by instances where he makes intentional decisions, however unorthodox they may be.

Disillusion with the Soviet system. In the waning days of the Soviet Union and the waning days of his youth, Yurka finds the whole enterprise to be rotten. Not only does it persist largely on inertia, but its symbols are hollow and its constrictions are arbitrary and unfair. His rejection from conservatory is not the result of poor performance, but the result of poor political connections.

Motifs

I actually quite liked the motifs. They might have been a little basic, but they were consistent and had satisfying payoffs.

Pioneer scarf: Yurka’s scarf is constantly disheveled and dirty, whereas Volodya’s is, like the rest of him, in pristine condition. There are consistent references to the scarf being “priceless” because it represents being a good Soviet citizen, although Yurka is quick to note that it only costs a few kopeks to make. It is also traditional for campmates to sign their scarfs at the end of session the way that American students sign their yearbooks. Volodya removes Yurka’s scarf and places it into their time capsule; this also happens before they have sex for the first time.

Music: Hurt by rejection from the conservatory, Yurka is willing in turn to reject something so integral to his personhood. It is only through his love of Volodya that he feels willing and wanting to return to the piano. He plays for Volodya during the play. He stores the sheet music for Tchaikovsky’s Lullaby in the time capsule. It is how Volodya greets him in the end, when they’re finally reunited.

Rain, rivers, water: recurring symbols of Volodya’s nearness. Wherever he is, there is water, an essence of life.

The willow: There is a willow on the bank of the river that flows through the camp. It’s long branches provide Yurka and Volodya shelter from the sun and the Soviet Union’s homophobia. It is under these branches that Volodya feels comfortable enough with Yurka to sleep on his lap. It’s here that Yurka begins to listen to classical music again, and where he identifies the Lullaby as the perfect accompaniment to the play. It’s where they make love and where they store the time capsule and where Yura returns, twenty years later.

Other Observations

I did not enjoy Pioneer Summer. I cannot recommend Pioneer Summer. but I do not regret reading it.

I recognize the importance and the impact of such stories in Russian for a Russian-speaking and Russian audience. I don’t want to diminish the risk taken by these ladies to craft and publish such a story.

I also recognize the massive effort that goes into crafting original fiction, regardless if it emerged from fandom first or not. Pioneer Summer, in more ways than one, feels like a first novel from amateur authors.

In addition to the lessons learned that I’ve outlined above, I will be taking away important lessons about the lived experiences of queer folk in Russia at the turn of the century. Consuming history and culture through literature is far more palatable than a textbook and there are certainly details that I will be adding to The Places We Call Sacred, given that two of the three leads are queer, born at a time when these conventions were being challenged. Remember, Russia, with its inhumane laws, is the same country that launched tATU.

This is not easy and I commend the authors for their work.

But y’all need to let my hand go.